Monitoring for Varroa Mites: More Information is Better

go.ncsu.edu/readext?1093550

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲This is a guest post by Lewis Cauble. Lewis is the NCDA&CS Apiary Inspector for Western North Carolina, a staunch advocate for beekeepers and honey bee research, and dedicated to keeping the honey bee population healthy and sustainable.

As an apiary inspector, I get to see a lot of colonies across WNC—the good, the bad, and the ugly. I estimate that 90 – 95% of the problems that I see in most beekeeping operations are related to just three things: Varroa mites, queen events gone bad, and feeding (too much or too little). I am always telling folks “You need good information to make good decisions!”

For example, in queenless colonies, simply adding a frame of brood to a colony can help you decide if you need to purchase a new queen. Add a frame of eggs and young larvae then come back in a few days to see what they did with it. Did they pull a few queen cells on that frame? If so, this tells you that they are hopelessly queenless and they could use some help in the form of a mated queen. Or, did they not pull a queen cell at all? This tells you that they are already raising a queen and you should probably sit on your hands for a bit—if you add a purchased queen to this colony, it is unlikely that she would be accepted, so don’t waste your money! Again, more information helps you make better decisions.

I am constantly recommending to beekeepers that they monitor for Varroa mites. Monitoring for Varroa is critical if your goal is to maximize bee health. A good monitoring program can tell you when it is time to control Varroa loads, it can tell you if you are too late to do so, it can tell you if your control methods were effective, and it can tell you if Varroa loads have spiked after your control efforts. All of this is good information.

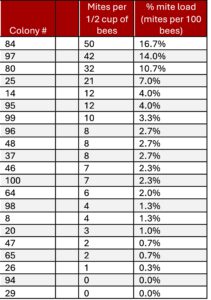

I would like to share with you some information that I gathered in my own personal apiary this summer that really helped me to make some good decisions. I have about 11 or 12 colonies in each of two yards. In early June, after removing my surplus spring honey, I went out and collected mite samples for monitoring. The good news is that most (66% of the colonies) were below the recommended infestation threshold (3 mites per 100 bees; see Table 1). Another 14% were just slightly over the threshold, between 3-4 mites per 100 bees. I can live with that. The bad news is that the last four colonies were wildly over the threshold at 7, 11, 14, and 17 mites per 100 bees, so immediate action was called for.

I decided to take the four colonies with the highest Varroa loads out of honey production for the rest of the year and immediately control the mite populations with ApiVar® (active ingredient amitraz). Of course, I had heard about amitraz resistance among some Varroa mites, but it had been working well for me over the last 8 plus years so I felt insulated from the issue since I had been a good steward of the product—I would use it only once in the summer and rotate with an ApiBioxal® (oxalic acid) vaporization in the winter, I was not buying or bringing in bees from outside (with potentially amitraz-resistant mites), and I was not mingling with other beekeepers that might be overusing ApiVar®. Therefore, I thought ApiVar® would be a good choice for these colonies that needed immediate attention, but others had warned that it might not work for me as it had in the past.

I went ahead with the application but I made sure I did some monitoring halfway through the application just to confirm that amitraz was reducing mite levels. Three weeks into the application, I took additional samples from each colony and things were looking good early on. Colony 84 went from a starting number of 50 mites per half cup of bees to 5 mites. Good progress! Colony 97 went from 42 to 7, also a good sign. Colony 80 went from 32 to 9, and Colony 24 went from 21 to 11. So some were progressing better than others, but I was only 3 weeks in to a 6-8 week application period so I was confident that things would be okay. Fast forward 4 weeks to my post-treatment monitoring. Colony 84 started the treatment with 50 and finished at 2. Not bad! Colony 97 started at 42 and finished at 0. Again, very good! Colony 25 started at 21 and finished at 7. Again, an improvement, but not what I was would call sufficient control. However, Colony 80 started at 32, went to 9 three weeks in to the treatment, but then finished at 21 mites!? That was a real red flag for me! In the past, my colonies typically came back squeaky clean after using ApiVar®. Therefore, moving from 21 to just under the threshold of 9 per ½ cup was, to say the least, disappointing.

This red flag set me on a path of further discovery. I called who I regard as the foremost expert on ApiVar® resistance, Dr. Frank Rinkevich at USDA-ARS Bee Lab in Baton Rouge, and shared my results from Colony 80 with him. I asked if he thought this was external mite pressure (from neighboring colonies) or Varroa resistance to amitraz. He was pretty convinced that it was from resistant mites, so he encouraged me to do some resistance testing to verify. I had worked with Frank on some ApiVar® resistance in the past, so I had the equipment on hand to do the work.

Frank’s resistance test is elegantly simple and easy. It might add a little time to regular monitoring, but you get even more information than just total mite load in the colony. You also learn if ApiVar® is likely to work in your operation. Starts with a quart-sized plastic food container, cut the removable top, and replace the hole with #8 hardware cloth (just as if you were building a sugar shake jar; Figure 1). In the bottom of the cup, hot-glue a square of ApiVar®. To perform a resistance test on the colony, place ½ cup of bees into the container then secure the lid. Flip the container upside down over a paper plate with a thin film of petroleum jelly on it to capture any mites that fall out. Hold the container above the plate with binder clips to give some space between the cup and the plate (Figure 2).

The test runs for 3 hours. At the end of the test, count the number of mites that fall onto the plate. These are the ‘susceptible’ mites (where ApiVar® killed them and they fell off their host bees). After that, wash the bees in each container with soapy water, strain the container contents through a mesh sieve (to strain out the dead bees but let the mites pass through), and count any remaining mites in the effluent. Any of these mites are ‘resistant’ mites after being exposed to amitraz. Simply divide the number of mites on the plate by the total number of mites (count from the plate plus the count from the wash) to determine ApiVar® efficacy. For example, in Colony 80 I counted 1 mite on the plate and 23 mites in the wash for a total of 24 mites, resulting in 4.2% efficacy (which is far below the required 70% efficacy that would make ApiVar® a worthwhile control measure). In other words, high efficacy is good (>70%), low efficacy is bad, and 4.2% is terrible.

I do need to mention that I performed the efficacy tests only after I had treated the colony with ApiVar®, so it is not exactly a fair comparison since the ApiVar® treatment had already removed most of the susceptible mites in the colony. Therefore, resistance testing should be done before any control measure. Colony 80 showed me that there was an amitraz-resistance issue in my operation, so I tested all of the other colonies from there.

The other colonies that had just been treated with ApiVar® (84, 97, and 25) all had low amitraz efficacy as well, but again this was not really a fair test since they too had just been treated. Colony 84 scored 13.3% efficacy, Colony 25 scored 36.4% efficacy, and Colony 97 scored 0% efficacy (but this was suspect since there were only 5 mites total, not enough to calculate a convincing estimate). Regardless, I believed these results likely pointed to a problem.

The other colonies in the apiary had not yet been controlled for Varroa with ApiVar®, and since I needed to do my pre-treatment monitoring anyways, I decided to do both my standard monitoring and efficacy testing at the same time. Of the 19 remaining colonies, only 3 had good efficacy results—Colonies 48, 29, and 20 ranged from 90% to about 94% efficacy, so ApiVar® would likely work for these colonies. In another10 colonies, there were not enough mites for the test to be valid, which is good news (mites numbers were not above the 3% threshold and therefore did not need to be controlled). The remaining six colonies, however, had plenty of mites and poor efficacy, with numbers ranging from 0% efficacy (Colony 99) to 58% (Colony 37). As good as ApiVar® had worked for me in the past, it is off the table for the foreseeable future since it does not adequately control Varroa loads. Therefore, I controlled my Varroa levels with ApiGuard® (thymol) this year.

My resistance testing also gave me some good information regarding my mite numbers in early August. There were certainly outliers on both sides of the curve, which is not surprising. The good news was that 47% of the colonies were at or below the threshold and I even had one colony with 0 mites (for sure an outlier!). Bad news is I had a colony at 37.7%, or 113 mites in ½ cup. This colony is pretty much already dead since it’s very hard to overcome such high mite levels. Another 26% of the colonies were between 3.7% and 6% infestation, and 2% were between 6.5% and 17.3% infestation. While I do have some colonies below the treatment threshold, I will treat all colonies at this time of year as I know what mite numbers tend to do in late summer and early fall.

Key take aways from my experience:

- Monitor all colonies to find the outliers. It is super important to identify and deal with colonies with high mite numbers. Sub-sampling the apiary is not likely going to catch individual outliers. In early June, I had only four colonies out of 21 that needed immediate attention, so sub-sampling would not have identified them. This is not unusual—in my monitoring from years past (and ample scientific research), I have come to expect that only 10-20% of colonies are going to be above threshold at any given time. Therefore, you have to sample all colonies to catch those that really need your help.

- Immediate post-treatment monitoring might not tell the whole story. Colony 84 went from 50 mites, to 5 mites, to 2 mites post-treatment, then back up to 30 mites in just 2 weeks! It would have been easy for me to feel confident that things were handled if I only did post-treatment monitoring, but testing just 2 weeks later showed that mite levels were back to 30 mites in a half cup. So, look out and don’t become complacent!

- Early June numbers may not predict early August numbers. My August outlier with 113 mites per half cup only had 8 mites per half cup in early June. This shows that Varroa loads can skyrocket in a hurry, so don’t assume that the population of mites always grows at a slow and steady pace. Immigration of mites from other colonies, age demographics of mites and bees, and other factors can significantly increase growth rates.

Again, remember that more information is better! Therefore, make monitoring a regular part of your beekeeping, including the test for amitraz efficacy. Together, your extra effort will be greatly rewarded with healthier bees.